History

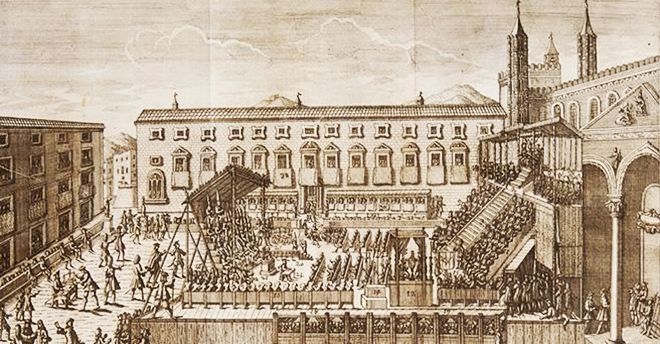

THE SPANISH INQUISITION IN SICILY

Since 1282, the year of the revolt against the French domination known as the “Sicilian Vespers,” the Kingdom of Sicily was annexed to the Crown of Aragon. From that point until nearly the end of the 17th century, Sicily’s political history was closely connected to that of Spain, which established the Tribunal of the Holy Office in Palermo. This was unlike the rest of Italy, where instead the Roman Inquisition operated.

THE COURT OF THE INQUISITION (1602–1782)

The tribunal, founded in Castile in 1478 with the aim of prosecuting Jewish heresies, was brought to Sicily in 1500 with the first inquisitors sent to Palermo. Palermo’s Royal Palace was the first base for the Inquisition Tribunal, but over time the Tribunal was located in various places in the city: the Castello a Mare, the Palazzo Marchese and Palazzo Ayutamicristo.

Finally, in 1602, the court was definitely transferred to the ancient residence of the noble family Chiaromonte, known as the Steri (from Hosterium). Behind the palace, an important building of severe architecture, was constructed, which hosted the secret prisons until 1782. It was in that year when the court was abolished. More than six thousand people were imprisoned here, including Jewish converts, renegades, apostates, necromancers, witches, Protestants, Molinists, bigamists, healers and healeresses.

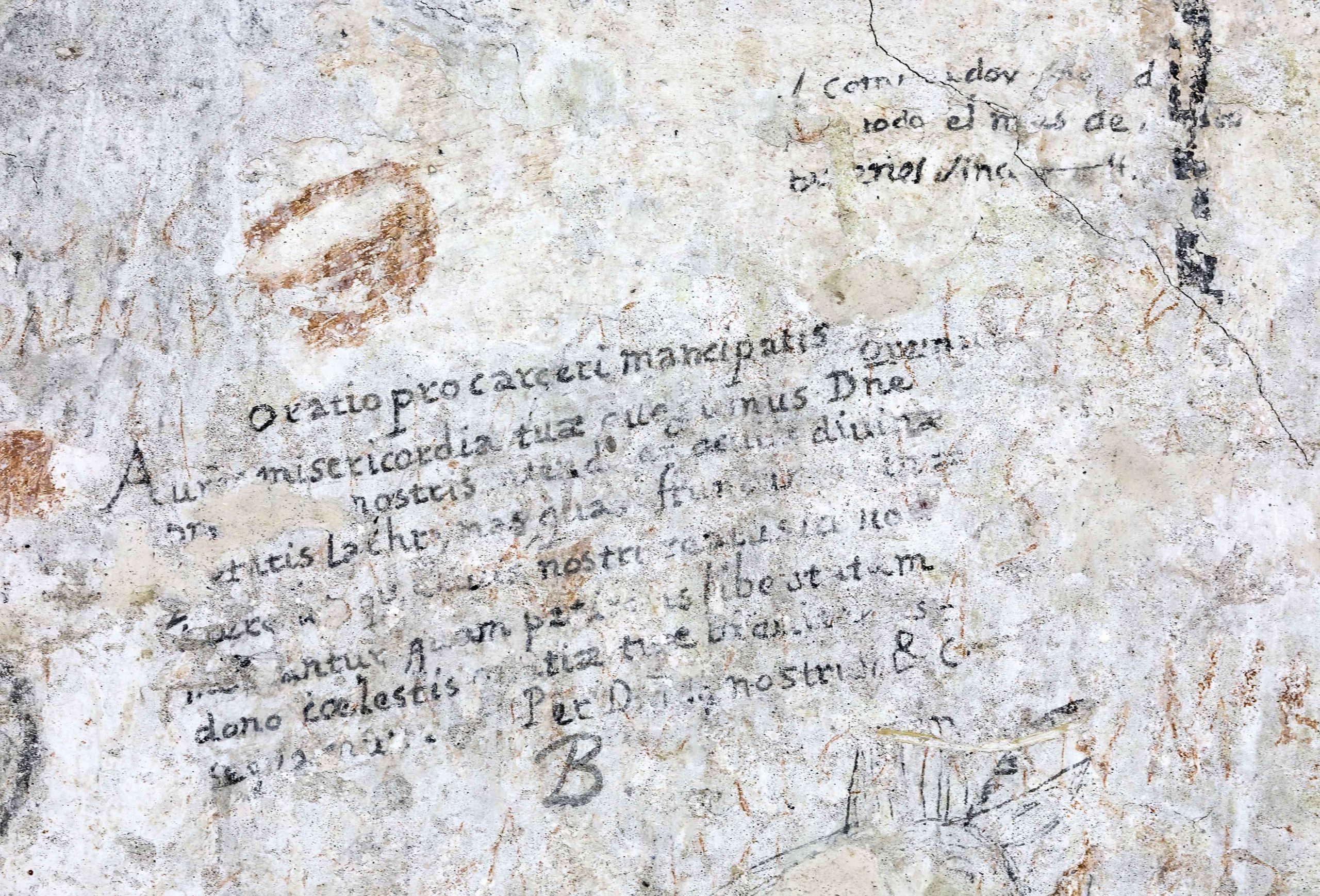

THE PRISONS GRAFFITI

Prisoners wrote and drew their suffering on the walls of their cells, creating a collective work of inestimable historical and human value, with an iconographic repertoire of extraordinary universal value. The graffiti were created using candle smoke, charcoal, powdered clay bricks mixed with milk, egg white, wax or organic materials such as blood and urine. They represented various kinds of images: crucifixes, madonnas, saints, biblical figures and scenes, maps, sailing ships, galleons, battles, shields and flags typical of 17th-century privateer naval war. Numerous drawings depict urban architecture and landscapes: castles, towers, ladies and knights, tree-lined avenues, monuments and balconies with flowers, plants and Baroque decorations. Furthermore, there are writings in different languages: Latin, Italian, English, Sicilian and Hebrew, which evinces the high cultural level of the prisoners. There are also verses, psalms, prayers, names, dates, exhortations, advices, and warnings: Coraggio! Non avere paura, io povero! manca anima…NEGA!

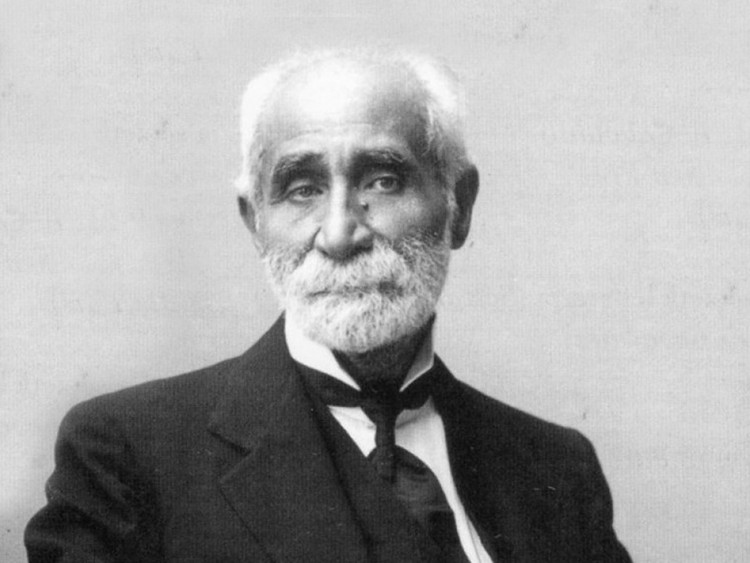

THE DISCOVERY (1906)

The graffiti, hidden and forgotten under layers of plaster, were rediscovered in 1906 by the Sicilian ethnologist Giuseppe Pitrè. He removed the plaster from the walls and discovered three cells entirely covered with writings, drawings and graffiti. Unfortunately, the graffiti were again covered and forgotten. In the 1970s, after the offices of the Rectorate of the University of Palermo were relocated to the Steri, the writer and journalist Leonardo Sciascia denounced, in an article published in the Corriere della Sera, the state of neglet of the prisons: “piles of dust and rubbish, broken glass, disconnected shutters. Pigeons made nests there and groups of rats were running everywhere. In the great hall with its painted wooden ceiling, an incomparable expression of the culture of an era… there was a constant fluttering of wings and rustling of mice among the papers and rubbish.” Later, the renovation of the building was entrusted to the Venetian architect Carlo Scarpa, who had already restored Palazzo Abatellis. Only in 2003, thanks to a restoration financed by the University of Palermo, the graffiti returned to light. In addition to the three cells discovered by Pitrè, others were discovered, making a total of 13 cells spread over two floors. Maria Sofia Messana studied the contents, reconstructing the stories of many of the recluses. The prisons are currently the object of numerous international studies and investigations.