Virginia di Bari

One of the first things children learn to draw is a house. A house as a whole of shapes: a square as basis, a triangle as roof, a rectangle as door. It is an elementary, essential vocabulary: a few simple geometric elements are enough to build a picture.

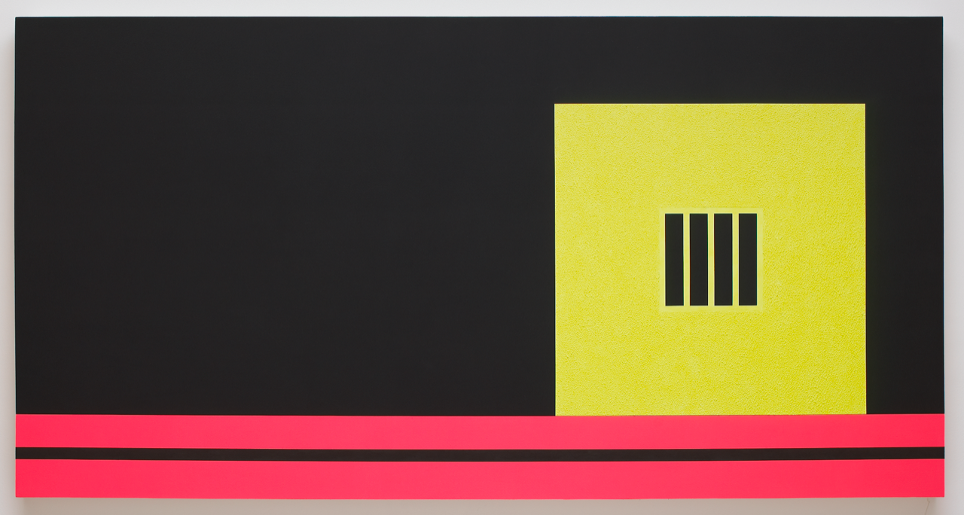

Peter Halley (New York, 1953), a key figure of American neo-conceptualism and neo-minimalism from the 80s, who made visual geometry the hallmark of his artistic expression, knows it well too. His artwork is a successful attempt to transcend the mere form. Thus overcoming minimalism, which claimed the non-objectivity of forms and their non-relation to the external world, Halley entrusts the image with a referent. In his iconic artworks on prisons entitled Prison & Cell, the New York-based artist explores the repetition, composition and evolution of geometric forms. Reflecting on these, and interpreting them as spaces of thought, he evokes through them other forms and structures: coercive ones of social control, namely cells and prisons. By thus establishing a relationship between abstract geometry, geometric abstraction and the world we live in, he connects us «borderless beings living of borders» to the condition of isolation inherent in our own existences.

Acrylic, fluorescent acrylic, flashe, and Roll-a-Tex on canvas, 147 x 284 cm. © Peter Halley

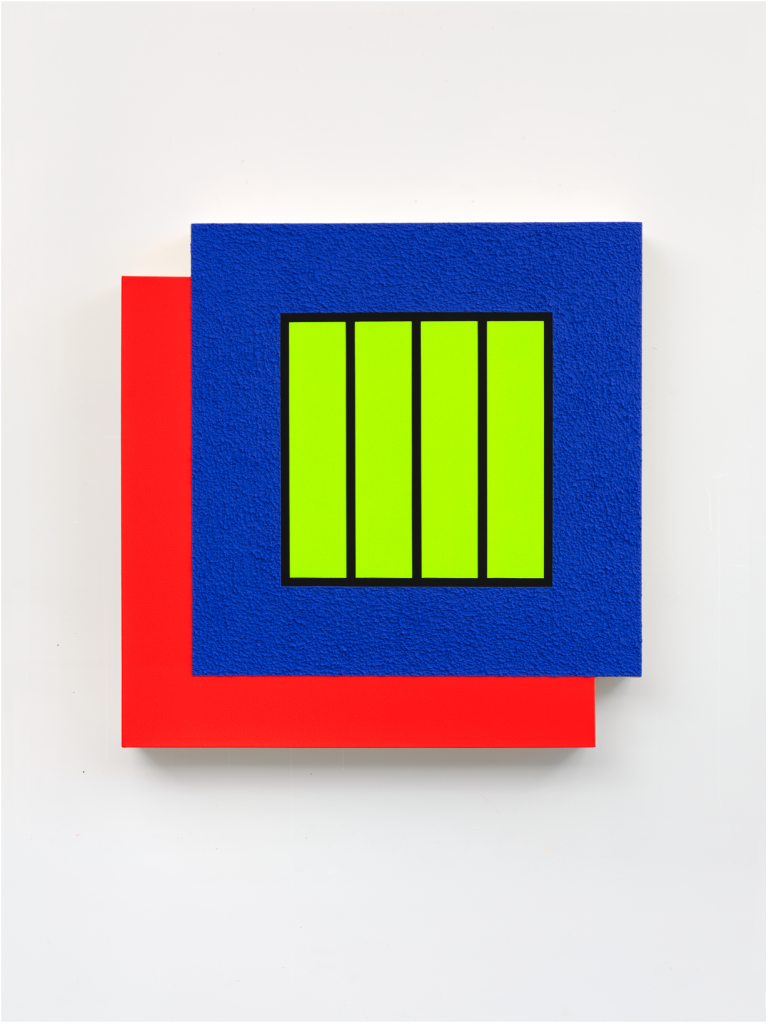

By employing such language consisting of repetitive forms, he shows us how geometry is made up of finite and determinate forms, and thus appears as a space of constraint that limits our expressive possibilities. «As I worked with that over period of a couple of years», the artist says during an interview by Giancarlo Politi in 1990, «I began to feel that it was quite a succinct way of expressing the space of our culture». On the other hand there is an outgrowth of this, and an opening to new fields of possibilities. «Having started to at geometry as confinement or segmentation, the next thing I began to think about was how movement was controlled in this kind of space and the kinds of connections that take place underground». In the same way children, after learning to trace the basic structure of the house, slowly add new elements, such as windows and smokestack, Halley in his artistic evolution inserts conduits, ducts, smokestacks: imagining connections, bridges of lines to form as many intersections, and connecting the squares to each other, he transforms his Prison & Cell into Prison & Cell with Smokestack & Conduit.

Acrylic, fluorescent acrylic, and Roll-a-Tex on canvas,

152.5 x 170 cm. © Peter Halley

Halley’s work forces us not only to stare at walls, but to train our gaze to look at the spaces and gaps that are like openings between bars, as avenues of escape or evasion. He invites us to observe the Zwischenraum, the space between those colorful prisons. Each with its own atmosphere, brings with it the possibility of being experienced in a unique and different way, thus illuminating a small space of freedom – and of expression.

Acrylic, fluorescent acrylic, and Roll-a-Tex on canvas,

112 x 112 cm. © Peter Halley

«The space that interests me is the human space, the space that human beings construct». Although too often we forget to consider it as such, the restricted space of prisons and confinement is also a human environment – as Halley seems to remind us figuratively with his paintings.

References

A. Del Puppo, L’arte contemporanea. Il secondo Novecento, Turin 2013.

M. Foucault, Sorvegliare e punire. Nascita della prigione, Turin 2014.

Peter Halley: Painting of the 1980s. The Catalogue Raisonne, exhibition catalogue, Geneva 2019.

Giancarlo Politi (Interview by), Peter Halley, in “Flash Art”, N. 150, January – February 1990.

G. Simmel, Ponte e porta. Saggi di estetica, Bologna 2011.